My first thought is not a very professional one: holy shit, Diane Ladd used to look exactly like her daughter. Now that I've got that out of my system, I can turn to the matter at hand.

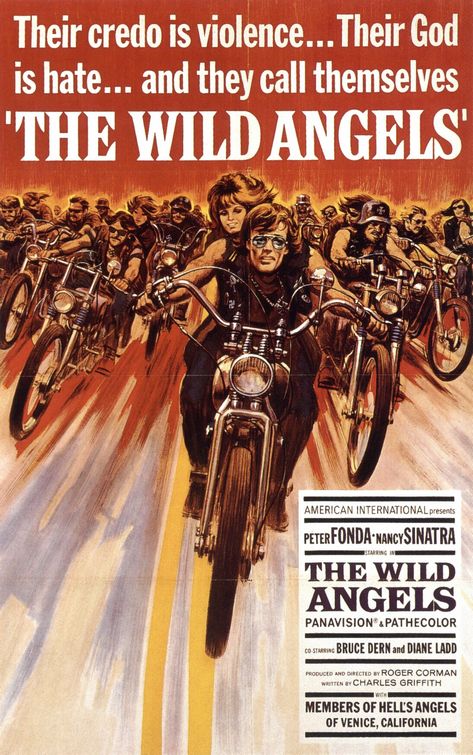

And the matter at hand is The Wild Angels, a film without which the subsequent history of cinema would look wildly different. This was the movie that really kicked off the biker film fad of the middle and late 1960s, not because it was first (biker pictures had been around for over a decade, though their popularity, and the popularity of the juvenile delinquent film more generally, began waning towards the end f the '50s; nor was it the first biker movie of the mid-'60s), but because it was by far the most popular, coming out at the exact moment when the rising notoriety of the Hell's Angels brought the subculture back into the limelight and made the time perfect for a savvy producer to exploit that culture for all it was worth (not incidentally, Hunter S. Thompson's Hell's Angels came out around the same time as the film). And oh, how The Wild Angels had a savvy producer, the savviest of them all: Roger Corman, who also directed, making the film under the aegis of American International Pictures, the most savvy of all bloodlessly mercenary independent film companies.

Anyway, that's not the reason the film had such massive influence, though it's a little bit interesting. The really important thing is that Corman had the good sense to cast in the film's lead role Peter Fonda, an unusually prominent figure in the burgeoning counterculture, owing to his rock-solid establishment bona fides (being the son of Henry Fonda would do that), mixed with his rather showy rejection of that establishment and his retrenchment within the West Coast hippie scene. This gave The Wild Angels an immediate shot of verisimilitude, and even more importantly, it got Fonda to thinking about deeper themes that could be explored using the mechanism of a biker film, and after a couple of years, that development of his onscreen persona and his offscreen philosophy, as initiated by this film, resulted in Easy Rider. And that film's seismic place in the development of American film is both well-known and undeniable.

The Wild Angels has to settle for being a pretty satisfying bit of grimy exploitation, not a cultural flashpoint and medium-altering achievement. And I suppose that's just the way Corman would have wanted it, him being one of cinema's all-time great pragmatists: I do not suppose that anyone would genuinely accuse him of having one-of-a-kind skills with the camera or actors, nor did he ever make a film that fundamentally challenged the way that stories could be communicated visually. But at his height, he was a genius anyway: rare indeed was the filmmaker who could so accurately predict what the audience would want, and when they'd want it, and then make a movie to fulfill that want for a budget that's closer to the cost of a new car than a "real" film production.

Clearly, The Wild Angels scratched some itch for watching the exotic, brutal adventures of barely-disguised Hell's Angels analogues (indeed "barely disguised" is giving the film the benefit of the doubt: the motorcycle club is named specifically in dialogue, and while we never see the Angels' famous death's head logo, the jackets the bikers wear are otherwise dead ringers for the famous, infamous Angel colors). Movies don't create genres without tapping into some deep-seated cultural current. And yet, the most conspicuous reality of The Wild Angels is that it was plainly made by old men who had no real idea about the subculture they were depicting. Corman himself was the very model of a square, far more concerned with how to squeeze every penny out of his projects, and when sociological messages crept into the films he wrote and produced, it seems to be mostly because he didn't see any profit in preventing his screenwriters from squirreling some themes away into the subtext. And he commissioned the script for the film from his good lackey Charles B. Griffith, who was, confessedly, one of the people who threaded some interesting subtexts into his scripts, but certainly couldn't count himself part of the counterculture. Much of the screenplay was rewritten by Peter Bogdanovich, who at least comes closer; but he was more of a film nerd than just about anyone else in a generation of film nerds. And from the onscreen evidence, in which authentic-sounding biker slang is wielded in the most stiff, inorganic way possible, we can go on and assume that nobody involved in putting that screenplay together was practicing anything like embedded journalism in making it happen.

The result - this is the key part - is that The Wild Angels falls into a foggy place where it at once wants to serve as a niche-targeting movie for all the young people beginning to voice the same sentiments about freedom and a lack of responsibility that we hear spoken by the characters onscreen, while pathologising that attitude as proof of the essential hedonist immorality of the characters espousing it. Basically, it's a piece of bikesploitation that deeply fears the dangerous potential of bikers and biker culture, but carries itself like a rabble-rousing cry of passion, in total sympathy with its characters, getting just at outraged at the injustices carried out against them as they are. It's a fucking weird mix of form and message, and I suspect that in the cold light of day, it means that The Wild Angels is an incoherent piece of nonsense; but since I am a Corman booster in good standing, I choose instead to take it as proof of his canny ability to make everyone happy at once. And since the film ended up a hit among the proverbial Kids These Days, he must have done a good job of it.

The Wild Angels is an early example of the "slice of life" picture, telling very little in the way of plot; it has an incident that shapes and guides the entirety of its hour and a half, but there's not nearly enough of that to make for a proper drama, and mostly what we see are people existing, responding to that incident but not with a great deal or urgency or, apparently, sense of things being terribly unique. And this too is part of the Corman school of stretching a buck: show as much talking as possible, at the expense of action, and if the talk is colorful and descriptive enough, nobody is going to very much care. The deal, basically, is that club leader Heavenly Blues (Fonda) has picked up some news that the missing bike belonging to his follower, the Loser (Bruce Dern) has been spotted in Mecca, Mexico. So the Angels say goodbye to their old ladies - Blues with his girlfriend Mike (Nancy Sinatra), Loser to his wife Gaysh (Ladd) - and discover that the bike has been stripped in a chop shop. In the ensuing brawl, the Loser snags a police bike, and a chase follows, leaving him shot, while the rest of the Angels escape. Sensing a trap, Blues nevertheless okays a mission to steal Loser from the hospital, and while they are successful, a nurse that some of the Angels tried to rape - Blues stopping them - identifies them. While the Angels head into Northern California to stage a funeral for their fallen comrade, the police begin to plot their capture of the notorious bikers.

Put it like that, and it sounds action-packed, but in the laconic, character-driven way it unfolds, it barely registers that there's any continuity between scenes at all. It's very existential in its feeling, in fact, certainly pushed in that direction by Fonda's restrained, uninflected performance. By the time the last scene rolls around, with Blues rather despondently giving up all hope - a precursor to the "We blew it" moment from Easy Rider, though played with more dramatic nihilism here than there - the film has been so fully saturated with an elegaic tone thanks to Fonda's work that even when it's at its most alarmed (such as in the borderline campy funeral scene with the Angels profane a church), the film feels more tender and sad than outrageous and exploitative.

But exploitative it is, and alarmist: from the opening credits, in which the "W" in "Wild" is cross-bred with a swastika, the film's insistent comparison of the Angels with brutality, anti-social behavior, and Nazi imagery is pervasive, and at weird odds to its emotional investment in their attempt to find peace, however they define it. I really can't explain it other than to assume that Corman and AIP were openly anxious to get both the bikers and the moralists on their side; that, or they only cared about being salacious and edgy, without reference to anything deeper than "what sells?" At any rate, I have no idea if the film's depiction biker culture is remotely accurate, either in its attempts at realism or its attempts at scare mongering; I just know that it's a weirdly moody, frequently dysfunctional drama whose completely casual depiction of the California underclasses has a raw, realistic tang that studio pictures had an immensely hard time matching, slow as they were to respond to the shifts in culture. And it is never less than fascinating, even when it's clearly not working on any level.

Also, it has a scene where Fonda, disgusted with himself, his lifestyle, the society that wants to tame him and his people, the planet that bore them all, stands alone outside at night, while yowling cats have been foleyed onto the soundtrack so loudly and aggressively - and a whole bunch of different cats, too - that the movie suddenly feels like it's drifted into some kind of avant-garde Catwoman riff. I have no idea how it fits into the rest of the film on any level, but I adore it: it never hurts to forget that, for all their fascinations, the films of Corman and AIP, together and apart, are still basically terrible, and moments like that are glorious reminders of how goofy low-budget B-movies could be.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1966

-The short Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree is the final animated film released by Disney before its namesake's death in December

-John Ford, a man's man of a director, ends his career with the decidedly uncharacteristic 7 Women

-Avant-garde artist and self-aware brand name Andy Warhol makes his mainstream breakthrough with Chelsea Girls

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1966

-Sembène Ousmane's Black Girl, a Senegalese-French co-production, brings sub-Saharan African cinema to international attention

-Italian master Michelangelo Antonioni makes the anti-thriller Blowup in England, documenting and autopsying the newly-forming counterculture

-The criminally under-appreciated and horrifyingly short-lived Soviet filmmaker Larisa Shepitko makes Wings, her first feature after graduating from film school

0 nhận xét:

Đăng nhận xét