A trio of reviews requested by Bryce Wilson, with thanks for his multiple contributions to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.It is not enough to begin at the beginning. We have to go before the beginning, to 1995, when the 26 episodes of

Neon Genesis Evangelion started to air on Japanese television. Telling the story of how skyscraper-sized humanoid biological robots called "Evas", piloted by emotionally damaged teenagers, fought off the onslaught of huge trans-dimension or extra-terrestrial or Christ knows what kind of creatures called "Angels", the show was an enormous hit. It was also a costly show, and one that took a turn near the end from subtly exploring emotional trauma to openly depicting creator Anno Hideaki's battle with depression. For these reasons, the last two episodes ended up in a place infinitely different than anyone might reasonably have expected it to end based on at least the first half of the show's run. And there were riots, literal actual riots with outraged fans defacing the building that housed Gainax, the studio which produced the series. Two years later, Anno responded to his baffled and enraged fanbase by remaking the last two episodes as the theatrical feature

The End of Evangelion, and in the process doing basically nothing to actually provide them with more clarity or closure.

But all this notwithstanding, the show was immediately entrenched in the hallowed annals of

anime as one of the series you absolutely, no possible way around it,

had to see if you cared about the medium at all, in Japan or anyplace else that the country's characteristic animation had made inroads. And five years after his second series finale, Anno was able to begin capitalising on the multinational enthusiasm for his signature project by planning an ambitious new retelling of the whole series. Collectively titled

Rebuild of Evangelion in English, the initial scheme as I understand it (which was altered) was for three theatrical movies to largely re-tell the series, with a fourth movie expanding into a whole new ending, with all-new big-budget animation that would flesh out the world, the characters, and the tech, with more detailed, lusher visuals. It took another five years for the first of these to come, and eight years later, the fourth film still hasn't been completed, though it has already gone far astray from a simple "remake the show" storytelling mentality, and it's a pretty simple and even necessary thing to regard

Rebuild of Evangelion as its own self-contained standalone narrative.

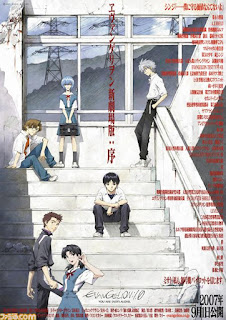

So with all that explanation out of the way, let's turn to the first of the three extant films, called... I lied, more exposition. The first movie exists in three versions, distinguished in English only by a number, and not distinguished in Japanese at all, that I can tell. First was the 98-minute theatrical cut from 2007,

Evangelion 1.0: You Are (Not) Alone. A film of the same length, with some re-timed color and other little tweaks, was released theatrically in Japan and on DVD worldwide as

Evangelion 1.01, with the same subtitle. And then a subsequent DVD expanded the running time to 101 minutes, and re-titled the film once more,

Evangelion 1.11. For the record, this review is based on

1.01, which I gather is the worst way to have gone about it.

But let's sweep all of that bureaucratic nastiness under the rug, and actually talk about the film, eh? Because when we get right down to it,

You Are (Not) Alone is a pretty delightful piece of contemplative science fiction. It begins in the best way possible for something that intends to be heady and, in its private way, "difficult": it simply drops us into a world that looks sick and ruined, with water the color of old blood and bedraggled foliage. And having set up that world in a series of wonderfully bleak establishing shot, it drops into a plot that started shortly before we got there, and really doesn't slow down enough for us to catch up. We can pick up what we need, but it's not till the midway point or so that there's anything like the usual cut-and-dried-exposition. By which point, in theory, we're so taken in by the characters and the unpredictable rhythm of their lives, the actual details of what's going on are at least somewhat beside the point. I gather that this has offended many, including fans of the series who consider it to be unduly rushed (and it sure as hell isn't slow). But the headlong pitch into a crazed world seems exactly right to me, and I find its ragged pace to be electrifying in its own right, different than series but not inherently better or worse - it's clearer and more urgent, but less organic in character-building.

The primary arena of the action is NERV headquarters, a bunker deep below the shiny, metallic, futuristic city of Tokyo-3. NERV is the UN's military response to the Angels, of which the fourth has just made its presence felt, endangering much of the city, but in particular the life of 14-year-old Ikari Shinji (Ogata Megumi), on his way to NERV at the order of his distant, dictatorial father Gendo (Tachiki Fumihiko), leader of NERV. He's found and rescued by Lt. Col. Katsuragi Misato (Mitsuishi Kotono), who immediately latches onto him like a big sister, and helps him find his footing as he trains to be the pilot of one of the Eva-01, though he has to be guilted into it. It's only when seeing a girl his age, Ayanami Rei (Hayashibara Megumi), badly damaged from her own recent battle against the fourth angel in the prototype Eva-00, that he agrees to shoulder the responsibility.

The English subtitle of

You Are (Not) Alone - chosen by the filmmakers, so it counts - speaks to its primary, almost overriding focus: this is not at all a movie about giant robots destroying giant inexplicable, almost indescribable things (the four Angels to crop up in the movie all look completely different from each other, and the sixth is defined by its absence of a stable form), which is at best its second-highest priority. Its third is on Christian imagery and overtones of the Biblical Apocalypse, which is transformed into something intriguingly weird as filtered through the perspective of a non-Christian culture (the use of Christianity in anime is something that I find endlessly fascinating, and about which I have absolutely no concrete knowledge). At times the use of Christian elements feels like Anno just pulled terms out of a grab bag without reference to what they mean (which American filmmakers do, like all the damn time, so I can't say that I actually have any problem with it), and so we have things like a command center named Central Dogma (also a term from biology, which doesn't make any more sense) and huge cross-shaped explosions when the Angels die.

The

first priority, though, is depression. A crippling, low-down depression that makes it virtually impossible to function. Shinji, as we learn throughout the movie, is almost incapable of feeling anything, and his motivations for his actions are almost exclusively limited to the single desperate hope that his father will offer him a word of praise. Meanwhile, he's so confused and disoriented by the kindness shown to him by Misato, it makes him feel even worse than he did to begin with. The action sequences in the film are as much a symbolic representation of how he comes to a better understanding of the people around him, as they are spectacle. They're still

some kind of spectacle, mind you, and frankly very good at it: the battle with the sixth Angel is an unusually impressive example of fluid CGI interacting with traditional animation, and it's as tense a pure action scene as I can think of in animation (which, honestly, isn't a very competitive race), while being tremendously imaginative in its use of the medium to add unpredictability to the villain.

The best thing about

You Are (Not) Alone is the way it marries its personalities - sci-fi action and blunt, raw character study (it is, scene-for-scene, far more intense in its study of Shinji's depression than the series was at the equivalent point) - without it feeling at all unnatural for them to exist in the same space. And it does it in a setting that, for all its grim trappings, is genuinely

fun: the characters aren't quite as complex as in the show, but they're generally livelier, the music gives a great deal of kinetic energy to even the most sedate moments, and the whole thing is utterly beautiful. The worst I can say about it is that the character animation can tend to be unusually limited, even for anime, but the backgrounds and use of color are so strong that there's never a case when the eye isn't busy anyway.

The sneaky thing about the movie, though, is that it doesn't end. It has a complete arc: Shinji's relationship to the people in his life evolves along a natural, comfortable line, and the final scenes round off the shape of the plot neatly enough that it feels like a structurally sound story. But there are almost nothing but loose ends, and the film adds more of them the closer it gets to the ending. It's easy for a movie to feel internally satisfying when it can kick of all of its most difficult elements to resolve down the road to its sequels, and while

You Can (Not) Advance is absolutely promising as the first movie in a series, it signs far too many IOUs to pretend that it's a great stand-alone movie in and of itself.

* * * * *

And wouldn't you know, the second part actually pays off some of those IOUS!

We have another title situation, though this time the English situation is more straightforward. There was a 2009 theatrical cut,

Evangelion 2.0: You Can (Not) Advance, running 108 minutes; the only home media releases in any country are of the 112-minute version titled

Evangelion 2.22. The original Japanese name for the film, meanwhile, is

New Evangelion Movie: Break, and I am told that the Japanese subtitles for the three movies are an overt reference to the structure of a Noh play. I am in no way qualified to talk about such things. But I do know that the word "break" can mean "to split away", and that's exactly what

You Can (Not) Advance does: while it starts off copying the original series with only some differences in flavor, by the time it ends, it's telling a completely different story using the same characters and themes.

So that being the case, let's not dwell on it. The second film, like the first, is mostly designed to tell a self-contained story, though while

You Are (Not) Alone describes a pretty clear individual arc around Shinji's emotional growth,

You Can (Not) Advance borrows most of its emotional resonance from the viewer's awareness of the first movie. Such is the luxury of sequels, of course, but I find it leaves

You Can (Not) Advance a bit less satisfying in its own right, since Shinji's development this time around lacks such an elegant shape. The first act, if you will, is assumed, rather than depicted. This is perhaps the reason that the second movie ends up more invested in narrative progression than character development, relative to the first movie and certainly relative to the show, which had the benefit of growing over a period of hours what here needs to be covered in an hour.

What this costs

You Can (Not) Advance in psychological subtlety, it earns partially back in intensity. The major new character in this film, German-Japanese Eva pilot Shikinami Asuka Langley (Miyamura Yuko), is a barreling force of antagonistic id, self-centered and arrogant and eager to lash out at the other teens for the unforgivable sin of being imperfect in her presence. She's written as a collection of bold strokes, a blast of energy where Shinji is compressed and Rei completely unknowable, and having her in the mix balances out the film's emotional energy well. Instead of the one-man study of the first movie, we have now a triangulation of three different ways of deal with self-doubt and the fear of loneliness, and the result is more complex and rewarding than

You Are (Not) Alone.

That's the idea, anyway. In practice,

You Can (Not) Advance is moving so quickly that something has to give, and for the most part, it's the depth of characters' relationships. It's clear that the essentialist feelings Asuka is blasting out constantly are there to distract everybody from what's going on in her head, and we're meant to be sophisticated enough to read her layers even when she's not showing them all at once. The thing is,

You Can (Not) Advance is so full of incidents and developments that just about everybody is presented in more or less equally essentialist terms. It's a character sketch, not a character study, and in that respect at least, I absolutely break from the consensus opinion that the sequel is a definite all-around improvement on the first film.

Generally speaking, though, the consensus is spot on. The "break" of the Japanese title can be read as more than just a break from the plot of the original series; in a similar fashion, the movie breaks from focusing on individuals as singular personalities to focusing on individuals as elements in a more cosmic framework. Particularly in the second half,

You Can (Not) Advance is more or less gunning to be an opera of sorts, using grandiose sequences and an impressively wide range of musical expressions to express a story on Big Themes expressed with Big Style.

At the most superficial level, this means more and bigger robot fights, and if there's one clear-cut reason to prefer the second film to the first, it's because the action is so vastly more impressive this time around. The ambitious scale of all the fights, both in their choreography and in the fearless way they mix traditional and computer-generated animation, puts even the most dazzling spectacle of the first movie to shame, and this one jumps to another level entirely during its protracted climax, a multi-stage battle involving a mixture of locations, characters, and depictions of fighting technique, veering from pure popcorn movie vivacity to abstract behavior mired in the twists of the series' elliptical mythology and expressed in art that seems to detach themselves from the movie to work as solitary images, like a comic book made entire of splash pages. It's gorgeous even when it's thoroughly baffling, which is more often than not; the other thing that happens besides bigger fights is more esoteric storytelling - if you noted that I haven't done much in the way of plot recapping for this second film, it's because the plot defies synopsis. It goes basically like, "Asuka comes in to upset the delicate emotional detente between the established main characters and strike up antagonistic sexual chemistry with Shinji, after which a long sequence makes deliberately no sense except that it's something to do with deliberately triggering the end of humanity, possibly to save humanity", with most of its conflict and stakes happening in a philosophical plane that's not always easy to parse, particularly since the film kicks so much of it down the line. I'll confess that this isn't not my favorite part of

Evangelion, not in the TV series and not in these movies. The film does its best to make the character development and the grand-scale storytelling depend on each other, but it's a little too easy for the focus to drift.

You Can (Not) Advance leaves a lot of raggedness in its pursuit of bigger stakes presented with a grander sense of mystery; there's an entire character, Makinami Mari Illustrious (Sakamoto Maaya), whose presence suggests that she's being put into place for later purposes rather than because the plot actually needs her; she feels throughout rather like she exists outside the narrative commenting on it. And like

You Are (Not) Alone, this film doesn't bother resolving itself, and compounds it by ending on a particular note of apocalyptic grandeur that is then directly contradicted by a scene that appears after the end credits. And this strikes me as sloppy storytelling more interested in the broad strokes than the fine details, anyway.

And yet,

You Can (Not) Advance did the one thing I absolutely needed it to: it drew from the character development of the first movie and sent the story and characters in new directions that feel entirely organic from what went before, giving Shinji in particular a more daunting set of internal and external obstacles to overcome in the process of proving to himself that he has value, is loved, and is capable of loving. Perched on the vantage point of 2009, it's not too hard to be optimistic that the next film could redeem this one as thoroughly as this redeemed the first, even though the story has expanded so much with so little clarity, that there's quite a lot more to redeem this time.

* * * * *

So much for redemption. The third and so-far final part of the

Rebuild of Evangelion series (the concluding fourth part is overdue with no release date in sight),

Evangelion 3.0: You Can (Not) Redo, doesn't merely fail to button up the holes left by

You Can (Not) Advance, it dances around clapping and laughing about how signally it fails to do so, how little it cares if that's what we might have been interested in, and how many brand new holes it's ripping open. It's quite an aggressive little beast on that front. The first two movies, even when they were incomplete, or confusing, or weighed down with too much murky spiritual philosophy, are still ultimately appealing and enjoyable films on their own right, but

You Can (Not) Redo finally goes over the edge to become simply frustrating and tedious and damn near unwatchable in stretches. It's a fans-only proposition, and based on the online conversation around the movie, even a healthy portion of the fanbase wouldn't give it the time of day.

This third film - still officially unavailable in North America, though rumors persist of an extended cut showing up one of these days, for sure this time - has the decency to seem merely mysterious and exciting when it starts, though the second those mysteries start to clear up, tit's easy to wish they hadn't. After almost causing the end of humanity but being stopped just in time by a mysterious figure watching the battles between Angels and Evas from the surface of the moon, Shinji is floating, unconscious, in space, still strapped in EVA-01. He's rescued by Asuka and Mari, but not without incident; their approach triggers a drone attack and the first of the film's grandiose action sequences, and thus comes the first point at which

You Can (Not) Redo started losing me. Consistently, the action sequences in these films have been the easiest part to like: conceived with great scope, animated with a beautiful mixture of traditional and computer-generated images, and given operatic heft by Sagisu Shiro's rich score, mixing symphonic chorales that all but beg us to be suitably bowled over by the size and severity of the fighting. Sagisu, at least, is still in top form:

You Can (Not) Redo has my favorite score of the three movies, richer than anything in

You Are (Not) Alone and not as undermined by thin, frivolous passages in

You Can (Not) Advance.

The action, though, is nowhere near the level of its predecessors. Throughout, the filmmakers' goal has evidently been to create individually meaningful shots rather than show smooth, continuous action sequences linked by clarity and easy continuity, but the fighting in the third film is actively difficult to follow, and in this first battle at least, there's no sense of scale. In the few places where it's possible to track whatever the hell is happening, the action is presented from angles that minimise the size of the Evangelion units, and without any physical context to compensate for it. A movie about giant robot fighting machines, in theory, has to do just one thing right, and...

Back to the plot, though. We'll learn soon, though perhaps not soon enough, that 14 years have passed since the end of

You Can (Not) Advance, during which time an organisation named WILLE has come into being in opposition to NERV, and Misato herself is one of its leaders. Shinji is treated with a profound lack of trust by his former friends and colleagues when he's not ignored by them outright, and retreats in the empty misery that's his default mode. At a certain point, he's rescued by Rei, and dropped on the surface of Earth, in the ruins of NERV headquarters, and it's here that he meets a young man named Nagisa Kaworu (Ishida Akira) - the same mysterious figure we've seen on the moon in the final moments of the last two movies. And here we get what amounts to an exposition dump, after two and a half movies finally learning more or less exactly what's going on. What's going on is a slurry of pieces from Genesis and Revelation mixed in a blender. Shinji makes some unbelievably stupid decisions and almost brings about the end of all life for the second time, leading the film's second and distinctly more coherent giant action setpiece.

The chief practical effect of all this is to shortchange the development of the characters (the series' best element to this point) in favor of doubling-down on mythology (which I, for one, would call its

worst element). And not only is this the least psychologically acute of the films, it actually works at cross-purposes to what has been best in the two movies preceding it: the hard-earned sense of family and comradeship between the insular, cripplingly depressed Shinji and Misato, Asuka, and Rei.

You Can (Not) Redo runs so hard from that, it's almost openly contemptuous of the earlier character arcs. And while the conversations between the hollowed-out Shinji and the kindly Kaworu are interesting - and certainly the strongest part of the film, both narratively, and even, though probably coincidentally, visually - that hardly justifies the zeal with which Anno and his colleagues abandon what had been working so well to that point.

It's a shambles at the level of writing, leaving its characters wrecked in the quest to do something needlessly bold with the mythology, and far too eager to leave plot holes hanging everywhere, possibly to set up the eventual fourth movie, and probably just because being mystifying was more fun than being cogent. At least

You Can (Not) Redo looks more or less attractive, though I find the character animation to be the least appealing of the films - it's brighter and sharper, but also more cartoony, almost, with bigger, gaudier expressions. Still, the marriage of animation styles hasn't looked better, and some of the effects animation is legitimately as perfectly executed as anything I have ever seen. That being said, it's telling that the most unique and beautiful sequence is one of the most primitive: a depiction of Shinji's feelings as he listens to Kaworu playing piano that uses line drawings and stills with lots of empty space and a reduced color scheme. In the midst of a bright and busy movie, the calm, reductive style of this sequence stands out, and it looks special in a way that all the glossy, ambitious art elsewhere in the film can't, simply by virtue of there being too much of it.

Looking handsome only goes so far, and it's not enough. This is basically the mash-up of

2001: A Space Odyssey and Michael Bay's

Transformers that nobody asked for, and which doesn't work much at all. It's visually chaotic and narratively confusing, which is perhaps a marriage of form and content, but not the kind we should be celebrating. The quality of the first two movies is enough to give me some hope that the eventual conclusion is heading someplace interesting, but after the almost uninterrupted joylessness of this one, I can't say that I'm champing at the bit for the fourth part to finally come out.